Gaze across the pristine green hills of Trnovo and you’d be hard pressed to find a single sign of civilisation.

And that’s precisely the point.

A Dubai-based property developer sees this clearing on Mt. Bjelasnica – home to part of the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Olympics – as a prime location to realise Bosnia’s biggest ever foreign investment: Buroj Ozone City.

By Matthew Brunwasser Business reporter

23 September 2016

- From the section Business

Image MATTHEW BRUNWASSER / This pristine Bosnian landscape is set to be be turned into a vast building site

The planned holiday city of 40,000 people will include private villas, luxury hotels, a shopping mall and a hospital. Its construction will cost a reported 4.5 billion Bosnian Marks (BAM) ($2.5bn; £2bn) and it should be completed by 2025.

Bosnia, which has Muslim majority, is one of Europe’s poorest countries and its people welcome all the foreign business they can get.

But the enormous size of the project – it equates to 15% of Bosnia’s GDP [gross domestic product] – is fuelling some unease.

Increasing numbers of Arab tourists and property buyers are coming in to the country, while investment by Western investors is shrinking.

What impact might this project have on the country’s development and culture?

Image BUROJ INTERNATIONAL GROUP / Buroj Ozone City will include private villas and luxury hotels

Image BUROJ INTERNATIONAL GROUP / Buroj Ozone City will include private villas and luxury hotels

Buroj International Group organised a celebration here for the ceremonial start of construction earlier this week, with speeches by Bosnian politicians and folk dancers, free grilled meat and non-alcoholic drinks.

Ismail Ahmed, the group’s chief executive, says he expects the project to increase tourism and investment in Bosnia, create thousands of jobs, and result in “a full city with full facilities for everything” that is open to everyone.

He claims the new properties will be accessible to Bosnians as well, with prices for private villas starting at BAM 2,300 ($1,300) per square metre.

“We have sent a message to the whole world that Bosnia is a safe place for investment,” says Mr Ahmed.

But will ordinary Bosnians be able to afford such prices?

Watching the event with a sort of hopeful scepticism, is Omar Krupalija, a clerk born 5km away. He says the investors are attracted to the beautiful and untouched landscape, the fresh mountain air and clean water.

“They often say that this part of the world is ‘jannat’: the Arabic word for paradise,” he says. “Bosnia is in such a state that we welcome any investment from anywhere.”

What’s important to Bosnians is that the investors act responsibly and deliver on their promises, he says.

“Like during the war, when Bosnia was under siege from all sides and the Mujahedeen came to help us. In that situation even if the devil came, we would have accepted his help.

“Economically, we are in the same situation today.”

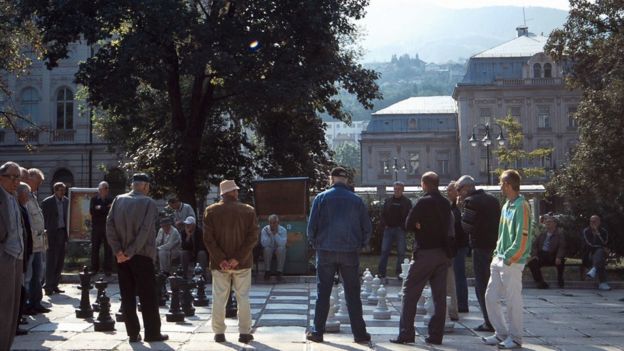

Image VELISLAV RADEV Time on their hands? Unemployment in Bosnia stands at 44%

Image VELISLAV RADEV Time on their hands? Unemployment in Bosnia stands at 44%

Economist Zarko Papic, director of the Initiative for Better and Human Inclusion, a Sarajevo-based think tank, agrees.

“Bosnia desperately needs foreign investment,” he says.

Monthly wages here average $475 (837 BAM) and the political stalemate between ethnic communities has paralysed the badly needed government reform process for years.

“Let’s say hypothetically that the project is implemented in full. That will be a good thing,” says Mr Papic.

“But the real question is: who will buy these properties? To me, this is still an abstraction.”

Gulf Arabs have been buying property around Sarajevo and prices have doubled in the last three years, Mr Papic says. The most popular spot is Ilidza, the leafy western end of Sarajevo tucked into the foothills of Mt. Igman along the Bosnia River.

Image MATTHEW BRUNWASSER / There are already Arab language shop fronts in Ilidza

Image MATTHEW BRUNWASSER / There are already Arab language shop fronts in Ilidza

Bosnians see Ilidza as an Arab enclave. Street signs now offer all sorts of business services in Arabic language: real estate, restaurants, dentists, travel agencies and souvenir shops. The Hollywood Hotel is one of the most popular places to stay.

In the hotel’s billiards room, a group of young Kuwaitis enjoy their last days of summer vacation before heading home. Fahad Alhunaidi, an accounting student says: “Now everyone in the Gulf countries is talking about Bosnia. They say it’s a new country with a growing economy. It’s not expensive. And it’s easy to communicate with people.”

While the new Arab-owned businesses, such as shopping malls and restaurants, don’t serve alcohol, secular Bosnians don’t seem concerned. Few worry that they will have to go far out of their way for a drink.

Nor are there concerns that the Arabs’ alcohol-free policy will be imposed on existing Bosnian businesses.

At the City Pub, one of the popular bars in the centre of Sarajevo, waitress Belma Eminagic, 25, is taking a cigarette break.

Image MATTHEW BRUNWASSER / “If I was an Arab, I would come and live here,” says waitress Belma Eminagic.

Image MATTHEW BRUNWASSER / “If I was an Arab, I would come and live here,” says waitress Belma Eminagic.

“Waiters and taxi drivers see them as walking money bags and treat them very well,” she says. “They say ‘hello, my brother.’ Sometimes they cheat them and sometimes they get good tips. When people treat them like a god, and everything is cheap, it’s really nice for them.

“In the beginning when they came here, they asked if we were Muslims,” she says. “When we said ‘yes’ they said very judgmentally: ‘But you are drinking and smoking?’ Now they accept us and have a nice time here.”

Bosnians say their anxieties are mainly economic. There are concerns that Arab buyers will dominate the property market and drive up prices for Bosnians. And that an increasing number of Bosnians will be working for wealthy Arabs.

“We are going to become their slaves, slowly but surely,” says Adin Bjelak, 30, a waiter, drinking a coffee in the cafe Balkan Express.

While Mr Bjelak has worked with Arabs and has had plenty of positive experiences – as well as some negative – his pessimism is more about Bosnia’s poor prospects than Arabs’ aggressive business practices.

He is also concerned about the cultural impact on Bosnia.

While Bosnians are European, he says, Arabs have different table manners; they speak more loudly in public, and are more likely drop litter. He admits that he and his friends refer to covered Gulf Arab women in black face veils as “ninjas”.

“It’s changing our culture because we are getting used to their lifestyle,” he says.

Image MATTHEW BRUNWASSER / Adnan Ducic outside Sarajevo’s 16th Century Gazi Husrev-bey mosque

Image MATTHEW BRUNWASSER / Adnan Ducic outside Sarajevo’s 16th Century Gazi Husrev-bey mosque

After prayer time at the 16th Century Gazi Husrev-bey Mosque, Sarajevo’s largest, Adnan Ducic is passing the time smoking rough Drina cigarettes. With a neatly trimmed beard, Ducic, 34, is unemployed – like 44% of Bosnians.

With typical Bosnian gallows humour, Ducic explains why only Arabs want to invest in Bosnia.

“The Arabs are new here, whereas the Europeans have been here for a long time,” he says. “When the Arabs get more experience with our state administration and our way of doing things, they will want to leave, too.

“We have a saying in Bosnia: ‘God please give us health, since everything else has already been promised to us.'”